Marketers often overlook America’s war veterans. But their attention could be worth fighting for.

Last year, Kodak and Wal-Mart hit upon a national co-marketing promotion that seemed so natural, one wonders why they – or anyone else – hadn’t thought of it sooner.

The partners’ in-store campaign tapped an overlooked demographic: American military veterans. For two weeks surrounding Veteran’s Day, anyone who brought a photograph of a veteran into a Wal-Mart store could make a free 5″ x 7″ reprint on a Kodak Picture Maker, a digital-imaging system that produces photograph-quality reprints. An additional copy was made for the store, which posted the photographs as part of a display honoring “Hometown Veterans.”

At the end of the local campaigns, each store shipped the photos to Kodak, which now has some 35,000 pictures of veterans piled up in its Rochester, NY, headquarters. The company plans to use them for some sort of national veteran’s tribute, according to Walter Parsons, sales manager for Kodak’s digital products. The pictures will likely be used in a montage and posted at the Kodak shareholders’ meeting, then made into a poster. Proceeds from poster sales will go to local veterans organizations, says Parsons.

Another in-store brand, American Greetings, chimed in on Kodak’s effort with an oversized thank-you card Wal-Mart customers could sign to veterans. The cards were donated to local Veterans Administration hospitals and town halls.

Conceived by Rochester, N.Y.-based agency Idea Connections, the promotion worked on several levels; its target demographic, seasonal tie-in, heartfelt appeal, local execution, and business cases all aligned. The campaign drove traffic into Wal-Mart stores, and Kodak increased awareness and first-time usage of its Picture Maker, which is currently installed in some 20,000 retail locations. The campaign’s feel-good aspect also didn’t hurt the partners’ brand images, either. “It was a neat way to show appreciation for their service to our country,” says Parsons.

It was the first time that either Wal-Mart or Kodak had targeted the veteran community (although it probably won’t be the last). But they’re not alone in that regard, because it’s tough to find many mainstream brands that consider veterans a hot demographic – despite the group’s size.

Bet on Vets There are an estimated 24.8 million veterans in the U.S. and Puerto Rico, according to the Department of Veterans Affairs in Washington, D.C. And they are relatively easy to target, since much of the segment is well-concentrated: 25 percent of all veterans live in California, Florida, and Texas. Another 15 percent reside in New York, Pennsylvania, and Ohio.

Statistically, veterans are a homogenous group: 95 percent are male, 57 percent are between 30 and 64 years old, and 89 percent are white. We’re talking white senior citizens who are primarily middle-class, blue-collar people.

Psychographically, however, veterans are more difficult to classify. Consider politicians – one of the more obvious groups trying to get veterans’ attention. But even vote-hungry candidates do not view vets as a block vote because of their many differences.

What most distinguishes veterans is the war in which they fought. The largest segment – one-third, or 8.1 million – served in the Vietnam War. World War II veterans comprise one-fourth of all living veterans, or 5.9 million. Another 4.1 million fought in Korea, and two million served in the Gulf War. Only 2,400 World War I veterans remain alive today. There are also 5.8 million peace-time vets.

“It is difficult to say that there is a typical veteran. They come from every walk of life and aspect of American culture,” says Jim Benson, spokesperson for the Department of Veterans Affairs, which has a $41 billion annual budget that funds a range of veteran benefits, from healthcare and home loans to vocational rehabilitation and education. While deep feelings of patriotism are a common bond, that’s only so effective as a rallying point for people who span generations, he says.

Another likely reason veterans have remained relatively unattractive to marketers is the group’s declining influence. The veteran population is shrinking at a rate of 1.5 percent each year, and thus does not hold the same lifetime-customer attraction of other juicy consumer groups like teenagers – or even Baby Boomers in general. By 2010, the total veteran population will have declined 19 percent to 20 million. One anomaly to note: As the overall veteran population falls, the number over age 65 will increase.

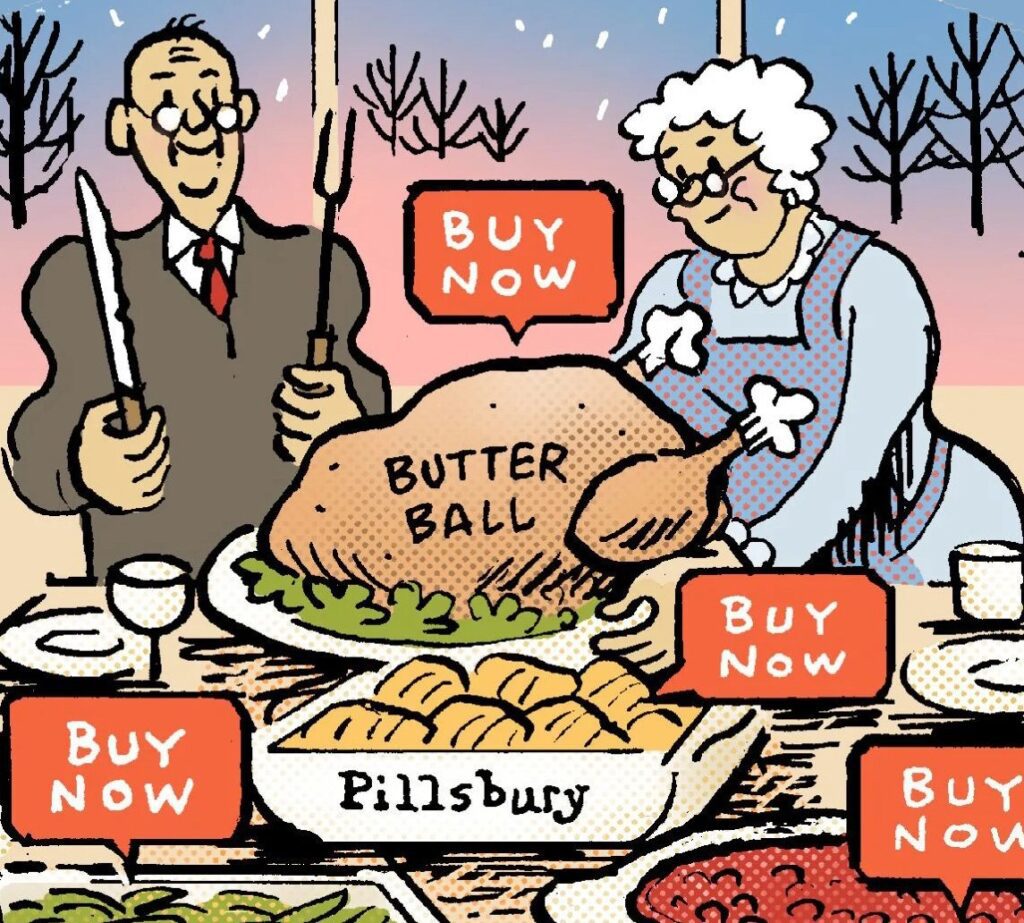

Sad Sack Marketing Veterans are, therefore, fodder for little more than an odd assortment of products ranging from caskets to coins. Most marketers target the group more for its age (as in elderly) than its common history or military affiliation.

Consider the companies that advertise in veteran-oriented magazines. Phonak, a hearing-aid manufacturer based in Warrenville, IL., is a regular advertiser in the publications of two leading veteran organizations, Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW) and the American Legion. Together, these publications reach about six million veteran households.

Although Phonak’s ads are the same ones that run in other senior-citizen magazines, the company does view veteran marketing as a strategy. “Our competitors are not targeting vets as aggressively as we are,” says Bill Wiener, whose firm, Advertising and Media Advisors, New York City, works with Phonak. Wiener says veterans are more likely to have hearing problems because their war experience exposed them to artillery fire and other loud noises.

Other VFW advertisers include casual clothing maker Haband; memorabilia companies that sell commemorative hats, pins and collectibles such as Rush Industries and Franklin Mint; outdoor and gardening products from Country Home Products; and period music producers Yestermusic. There is also a host of attorneys.

That’s hardly a sizzling cast of characters – unless you make a living selling the ad space, like Harry Church of GLM Communications in New York City. Church sheds some light on what moves VFW readers. Veterans, he says, are most responsive to direct-response ads – mail order, coupons or toll-free numbers. That’s because the majority live in “C & D” counties and do not have easy access to a lot of retail shopping. Also, VFW’s magazine readers are mostly veterans of World War II. “It’s an older, rural demographic,” says Church. “It’s a lot of people looking to maintain camaraderie.”

No Show of Support And it’s a group that goes to conventions. But VFW and American Legion events aren’t flush with mainstream sponsors, either. Only at VFW’s 100-year anniversary convention last year in Kansas City, MO, did big brands make an appearance. Deloitte & Touche, Pfizer, Parke-Davis, and Conseco were among the large companies that hung banners, hosted events, and helped underwrite entertainment including a Kenny Rogers concert. “That was a departure from our normal convention,” says Steve Van Buskirk, VFW’s director of communications. “Generally, we like to pay our own way.”

In fact, the VFW often rebuffs corporate sponsorship opportunities. “We get approached occasionally by the tobacco industry and beer bottlers, but we’re downplaying [those products] because they do not provide the image we want to convey,” Van Buskirk says.

Indeed, Coors Brewing Co. made veteran-specific beer cans years ago. It no longer singles out the group.

The American Legion, a nonprofit group with 2.8 million members, holds 18 annual meetings and runs one national convention that draws 15,000 veterans and family members. This year’s 82nd annual convention was held in Milwaukee. Other than vendor booths set up by the local travel and convention bureau, there wasn’t a single sponsor for the event. The reason? There is none.

“We don’t currently accept sponsorships, and I’m not sure why,” says Dick Holmes, the Legion’s national convention director. The good news: Holmes says he is willing to listen to ideas.

Political consultant Larry Hart says veterans are receptive to issues that are relevant to them, such as healthcare benefits and military policy. That’s why healthcare and pharmaceuticals are more obvious candidates for veteran outreach.

Consider the awareness campaigns surrounding hepatitis C, the potentially fatal virus spread by blood-to-blood contact. Veterans are more likely to have hepatitis C, particularly those who served during the Vietnam era. The virus has been a platform for Miss America 2000 Heather French, whose father is a disabled vet. When French takes her message – “Helping Veterans Fight a Silent Enemy: Hepatitis C” – from city to city, the Miss America Organization efforts are supported by pharmaceutical giant Schering-Plough. The Kenilworth, NJ-based company makes drug therapies that help treat the disease. Sales of those drugs (which are used to treat other illnesses as well) reached $674 million in the U.S. last year. But the company is more a passive than active promoter. “We do not tell organizations how to spend the money” that the company provides, says director of communications Bob Consalvo.

With their dramatic pasts and their disparate futures, veterans are both a delicate and fertile demographic. Perhaps the one shared trait that marketers can safely tap into is pride. “They are a close-knit group. For some, their war time history is their primary sense of identity,” says Hart.

More important than policy or politics, a feeling of appreciation for what the veterans did for the U.S. is a powerful message, and could be a powerful sales tool. Perhaps that’s why the Wal-Mart campaign resonated so strongly.

“After the promotion, I called my dad who served in World War II and said, `Thanks,'” says Kodak’s Parsons. “No one had ever said that to him before. Just think about how many other vets that applies to.”

Can patriotism translate into brand allegiance? Maybe it’s worth finding out.