“Big data” is the new hot topic, the latest hook to sell marketing books and webinars, and I can’t wait for it to go away. Not because there’s not a large kernel of truth buried in it: Marketers can make very profitable use of the amounts of data they may already hold on their customers, parsing it or combining it legitimately to segment new demographics or uncover buried customer profiles.

“Big data” is the new hot topic, the latest hook to sell marketing books and webinars, and I can’t wait for it to go away. Not because there’s not a large kernel of truth buried in it: Marketers can make very profitable use of the amounts of data they may already hold on their customers, parsing it or combining it legitimately to segment new demographics or uncover buried customer profiles.

But elevation to buzzword status blurs the edges of a concept, and “big data” in particular carries inherent limits that marketers will violate at their peril.

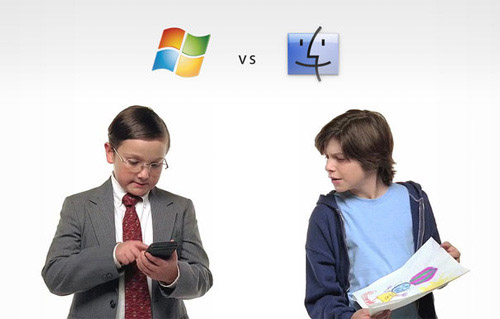

As a case in point, look at Orbitz.com. A Wall Street Journal story in early July revealed that the online travel search engine was displaying different, and pricier, hotel search results to customers who were detected as logging into the site on a Mac rather than a PC. In defending the practice, CEO Barney Herford said that data collected by Orbitz showed that Mac users were 40% more likely to book at 4- or 5-star hotels than their PC counterparts.

I’m sure the data did show that. What it didn’t show– because Orbitz didn’t ask– was how many of those Mac users would be hopping mad to learn that because they plunked down a bit more for an Airbook, they were now being shown specially targeted search results in categories that had nothing to do with electronics.

What made the Orbitz example to me (and apparently to hundreds of respondents to the WSJ article) was the popular perception that Orbitz operates as at least a hybrid version of a search engine. Users presume that it will offer the best results based only on the parameters they enter—not the data Orbitz can append using additional behind-the-curtain filters, such as the type of device they’re logging in on.

Just to clear away the obfuscation, nobody is saying Orbitz charged Mac users more for the same hotel package. That would be illegal.

Equally, no one in marketing will dispute that Orbitz, or any other web operator, has the right to serve up ads based on previous buying behavior– if it’s done in a way that doesn’t creep customers out. After all, those ads are based on my actual past views and activities. As long as there’s a clear way to opt out of being tracked, I will probably find such targeting relevant.

It’s even defensible to segment customers based on their devices in certain circumstances. Like all iPad users, I’m accustomed to getting ads that assume the hotels I favor feature infinity pools and hot-stone massages. Simple use of the device marks me as “high value” in the aggregate. I wish it were true, but I get it.

After all, there’s a reason Mitt Romney’s reaching out to his support base with a smartphone app rather than the more down-market SMS channel.

After all, there’s a reason Mitt Romney’s reaching out to his support base with a smartphone app rather than the more down-market SMS channel.

But those are ads, downloads or personal choices that I control: I know enough to overlook them if I’m not interested.

But content other than advertising is supposed to be served up with my preferences in mind, not the marketer’s. And the perception that marketers are manipulating actual query results because of what they want me to buy and how much they think they can persuade me to spend

It calls for one more recital of Quinton’s Law of Marketing: “Just because you can do it, doesn’t mean you should.” In the age of Big Data, that’s truer than ever.