Let’s play a game of Is It Advertising or Promotion?

Coca-Cola commits some $50 million of its marketing budget to cash prizes for consumers who find ATM cards in cases of soda. Its summer ad campaign tells consumers how to use Coca-Cola cards to get discounts at local restaurants and movie theaters.

The “got milk?” folks at the California Milk Advisory Board find out teenage girls are wallpapering their bedrooms with milk mustache ads, so the board gives away trading cards and screensavers of the ads at summer festivals.

Taco Bell pits its chihuahua against Godzilla in a $50 million campaign that sells an instant-win sweepstakes with Gorditas on the side. “Here, lizard, lizard,” the little dog croons. A huge reptilian shadow falls over him and he quips, “I better get a bigger box.”

Better get a bigger box, all right. The old one – the TV set – isn’t big enough to build a brand all by itself these days. Yo quiero integrated marketing.

Below-the-line disciplines are booming thanks to pan-business-world adoption of brand management, the strategy that asks every marketing dollar to build image and sell product at the same time. Companies from packaged goods and automotive to electronics and financial services have made branding the core of their marketing strategies. Advertising and promotion are overlapping like never before. Take Coke’s ATM cards: It’s brand image, all right, but it’s image with an offer.

In the 10 years since brand management began, marketers have come to realize that the strategy requires true integration of marketing disciplines. That lets promotion move into the driver’s seat, because it emphasizes measurable results from branding. In a quarter-by-quarter business atmosphere, promotion is the engine that drives the numbers.

“Advertising hasn’t changed, it just has more respect for the results other disciplines can deliver,” says Ray Gillette, president of integrated services for DDB Needham in Chicago. “Historically, brand management managed the advertising. Today brand management looks at strategy first, then media.”

Promotion, direct marketing, and events are taking over brand-building chores once the exclusive domain of ad agencies. So we ask the question: Is advertising’s long run as the centerpiece of marketing about to come to a close?

Sharing the limelight First, take a pulse: Ad spending is up 2 percent so far this year. At that rate, measured media could rake in $74.7 billion for 1998, according to Competitive Media Reports. At the same time, promotion spending is up 11 percent to $79.4 billion – not including an estimated $152 billion in trade promotion. Trade promotion still accounts for some 48 percent of the marketing pie, according to Cox Direct’s Annual Survey of Promotional Practices[recheck figs from new report]. Media advertising takes 27.4 percent of budgets (consumer promo is 24.9%), but nearly 40 percent of manufacturers’ media weight “is designed to support consumer and/or trade promotions objectives as well as brand equity,” Cox reports.

Next, define your terms.

“If you define advertising as the big 30-second extravaganza on mass-reach network TV, yes, it’s dead,” says Alan Gottesman, head of West End Consulting, New York. “But that’s not all that advertising does. The array of services that ad agencies perform is still the center of marketing strategy.”

“For most packaged goods marketers, advertising will always be the crown jewel of communication because there’s a direct relationship between how and how much you advertise your brand and consumers’ desire to buy it,” says Bob Berenson, president of Grey Advertising in New York City. “Advertising hasn’t been that crown jewel for non-packaged goods. [These marketers] maximize sales by integrating their brands seamlessly into the fabric of consumers’ lives. Different disciplines do that differently.”

No single discipline is up to the task of building brand image, sales, and retailer relations all at the same time, but promotion shops may be better suited to meet the challenge than traditional ad agencies.

“The unique thing about promotion and direct marketing is that you really have to know a brand’s business, not just what the brand stands for,” says Larry Deutsch, senior vp-business and strategy development at Wunderman Cato Johnson, Chicago. “It’s one thing to make a brand promise; it’s another thing to deliver on it.”

Like milk, for instance. Dairy Management Inc. – the folks who put “got milk?” ads on TV – and the milk mustache folks at the International Dairy Foods Association are worried that their combined $180 million in advertising isn’t selling milk. Sales were up only about 1 percent last year, a poor return on such a hefty ad buy. As the associations hash out whether TV or print ads work better, this year IDFA moved beyond awareness ads with recipe-based promotions that show new ways to use milk.

This summer, the California Milk Advisory Board, which created “got milk?” and licenses the ads to DMI, learned girls were collecting milk mustache ads. So it started handing out ads, screensavers, and trading cards featuring characters from Purple Moon CD-ROMs to pre-teen girls at fairs and summer events in California, and nationally via a Milk Mustache-mobile and two Web sites, www.whymilk.com and www.purple-moon.com.

Marketing execs agree advertising is essential to building a brand’s promise and its personality. What’s changed is that promotion and direct marketing – disciplines that build customer equity – are taking center stage alongside advertising. The new mandate of marketing is to deliver consumer experiences that deepen each shopper’s relationship with the brand.

The crucible is the retail environment. Stores have become such a hot branding medium that the savviest marketers have opened their own. Niketown. The Disney Store. Chrysler Corp.’s Great Cars, Great Trucks store. Starbucks has eschewed advertising for in-store merchandising to build its brand; does anyone not recognize the name?

Promotion grew up in the store, while advertising ignored it. So we ask a second question: Do ad agencies know marketing strategy well enough to compete with the new breed of multi-discipline marketing shop that promo agencies are poised to become?

The agency scramble The pressure to build image and sales comes from serving both Wall Street and consumers, who love brands and bargains.

More marketers recognize that “brands are the sum total of all communications; the goal is to build brands and customer relationships,” says WCJ’s Deutsch. Under that dual mandate, “it takes more work to determine which [agency] should take the lead on an assignment.”

The growing ambiguity has agencies of all stripes scrambling for the same assignments.

“There’s so much graying of the core focus of an assignment – it could be advertising, promotion, or direct,” says Marie Roach, manager of special projects for Chicago-based Frankel & Co. “It could be shepherded by any of those agencies. We want to be sure we get our share of those assignments.”

To that end, Frankel spent six months benchmarking its competition in several disciplines. Its conclusion: “Watch your backside,” Roach says. “Don’t be naive about who the competition is. You can’t look at the PROMO 100 list and feel content.”

Everyone wants in on the integrated pitch. Ad agencies, promo shops, and even premiums suppliers are feverishly buying or cultivating disciplines to complement their core expertise. Promo execs sitting at the pitch table with their sister ad agencies find themselves more central to the conversation as ad shops turn to promo types for their expertise at retail.

Gottesman blames fragmented media. “If 30-second spots still worked – if they ever did – people would still do it,” he says. “But media alternatives have gotten to be more difficult, so marketers have had to accept the legitimacy of other [tactics] that they wouldn’t have otherwise.” Hence the popularity of events, the Internet, and in-store media.

Ad agencies feel threatened by consultants horning in to help clients set brand strategy. The client rift dates back to the recessionary early ’90s, when agency staff cuts weakened agency skills and relationships with clients, says John Wolfe, spokesman for the American Association of Advertising Agencies, New York. Marketers “felt like they couldn’t turn to agencies as partners anymore,” and turned to consultants instead.

Gottesman says ad agencies lost their edge when their work became a commodity. As marketers farmed out creative to boutiques and media to buying services, agencies “were no longer the man behind the curtain doing it all,” he says. “They turned into the guy who shows you a menu.”

Still, adds Wolfe, “Agencies know their ace in the hole against management consultants is creativity. Agencies have the idea people to come up with words and pictures to solve brand-oriented problems.”

That raises two more questions. Do ad agencies feel threatened by promotion shops, which also have creative departments? Or are ad agencies getting back to the client’s table as marketing strategists by adding promotion and other below-the-line services?

Neither, Gottesman contends. Promo shops are no threat because “their portfolio is executional, not strategic. They get called in after certain decisions are already made. A promotion agency might be able to tell you whether to make a Western omelet or a Spanish omelet, but the eggs are still broken in the bowl when they come into the room.”

Maybe. But ad shops are still rounding out their services with events, direct marketing, and promotion, either buying or networking their way into these discip lines. Agencies quietly admit that the hoops they’re jumping through are the result of clients’ embrace of brand management.

“The biggest weakness in brand management is rotation,” says Grey’s Berenson. “Every brand manager feels he has to put his own stamp on the brand to get corporate recognition, so he throws out what’s been done already. It causes a short-sightedness that’s almost as bad as having to show quarterly profits.”

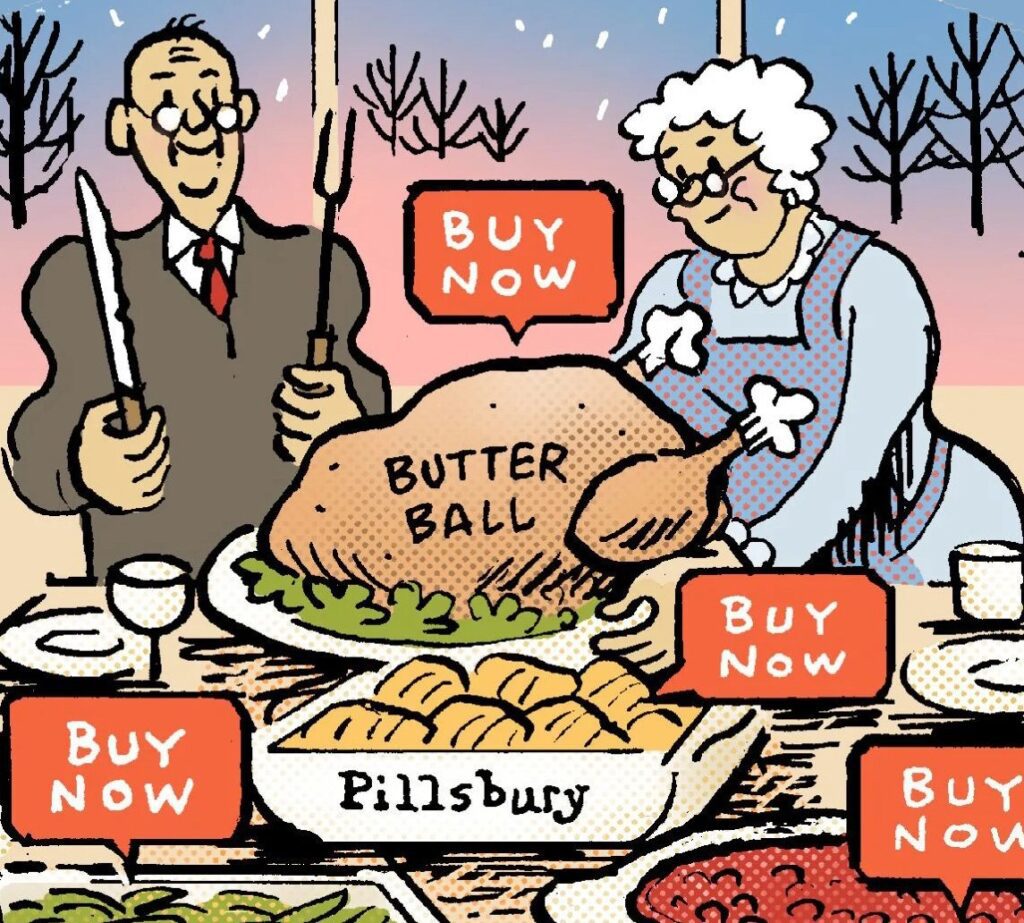

Consolidation fever Brand management has streamlined marketing so much that companies are dishing up bigger assignments to fewer agencies. Within the last two years Pillsbury, Miller Brewing, Citibank, Danone, Nestle, and Coca-Cola cut their promo shop rosters. Kraft Foods just finished its consolidation (see box on page TK). Such marketers want to work with fewer agencies that are big enough to handle the business, diverse enough to offer several marketing disciplines, and smart enough to help set brand strategy.

“Ten years ago, clients would say ‘We need a sweepstakes targeting X audience,’ ” says Frankel president Jim Mack. “Now they say ‘Here’s our brand; what’s the best way to take it to market?’ “

Pillsbury’s agency consolidation late last year typifies the shift to stronger promotion. The Minneapolis-based food giant revamped its entire promotion process while consolidating a reported $100 million late last year with three agencies: Clarion Marketing (Green Giant and Progresso brands); Dugan Valva Contess (group corporate events); and Ryan Partnership (Pillsbury brands). Pillsbury had used internal freelance promotion planners, as many as 100, to develop promotions. Planners reported to Pillsbury’s marketing services group, and tended to hire small local shops to execute single-brand promotions.

Sources outside Pillsbury say the system fostered disjointed strategy and weak creativity, so Pillsbury eliminated most planners when it hired the three agencies of record. Pillsbury execs won’t comment on the review, but sources say the company requested proposals from about 20 agencies last fall, then fielded a credentials pitch from about eight. A case study narrowed the field to fewer than five shops. The three winning shops split about 80 percent of Pillsbury’s brands; the remainder, including Haagen-Dazs, continue to be handled by internal freelancers. The consolidation brings “more continuity to promotions,” says Pillsbury spokeswoman Liz Hanlon.

Companies are naming promotion agencies of record with gusto. AORs have more strategic input and get fewer 11th-hour calls for a quick tactical fix. Such status gives promo agencies the luxury to focus on brand management and play on the same field – and in the same corner offices – that ad types have long peopled.

“We’re dealing with presidents, general managers, vps of marketing now, instead of brand managers,” Mack says. “That changes the way we work, and the way we’re compensated.”

WCJ credits its brand focus for recent assignments from 20th Century Fox and Avon. Fox’s Filmed Entertainment division named WCJ agency of record for film tie-ins. The Chicago agency began work on 1999 films in June, following Fox’s review of traditional promo shops.

Avon hired WCJ in June to handle its international sponsorship of Celine Dion’s 26-city tour. The event-management assignment may be a foot in the door for future Avon work. Dion’s manager recommended WCJ to Avon because he was impressed with how the agency negotiated cell phone marketer Ericsson’s title sponsorship of the tour. (Ironically, Ericcson hired a different shop to handle its tour events.)

“We didn’t just approach [the pitches] from a promo standpoint,” Deutsch says. “Promotion, direct marketing, events are all key contact points with consumers to reinforce the overarching brand promise. We’ll never be the lowest bid, and that’s not our intention. We bring greater value because we’re not looking at the brand through one lens.”

WCJ teamed with sister ad shop Young & Rubicam to pitch Ford’s Lincoln Mercury division, and was named agency of record for event marketing in July. WCJ had be en working on cycling and golf programs for Lincoln Mercury, and Y&R handles ads. Y&R’s Detroit office set new account teams for all its clients with reps from WCJ, Y&R, and P.R. shop Burson-Marsteller; group account directors come from the discipline a client uses most.

Gage Marketing Group also is expanding its strategic work. In July Gage sold off its low-margin, high-overhead fulfillment business to AHL Services to concentrate on building the lucrative front-end marketing strategy. The Minneapolis company is shopping for agencies. It now has four, handling direct marketing, database management, and promotions for clients such as Ford, Disney, American Express, Barnes & Noble, and Packard Bell. Gage is negotiating to buy at least one research firm, is shopping for a creative promotion shop (ideally in the Midwest), and is eyeing Internet agencies.

“We want to get into research and build databases,” says Gage TK Belle. “The players entering direct marketing [and database management] now are mostly behind the curtain – IBM, Andersen Consulting, accounting firms who’ve finally figured out there’s more to life than transactions,”

As clients like Ford zero in on consumer relationships, savvier direct marketing becomes core to brand growth.

Tchotchkes, my foot Promotion execs who are used to being dissed by ad agencies are looking down their own noses at premium suppliers breaking into strategy. Agency brass pooh-pooh the notion that companies like Cyrk-Simon Worldwide and Ha-Lo Industries can compete on a strategic and creative level. Well, their clients think they can.

Hot shop Upshot has been courted by a bunch of ad agency holding companies, but it was Ha-Lo that appealed to the $35 million Chicago agency. “It’s rare that a holding company’s advertising, promotion, and event agencies all work together on the same client business,” says Upshot president John Kelley. “Having all these agencies under one big roof only lets a holding company garner a bigger share of total marketing dollars out there. That’s good enough for Wall Street, but is it enough for clients?”

Ha-Lo, on the other hand, can expand brand marketing, Kelley believes, by adding new disciplines and new countries to its existing $338 million business. The Niles, IL-based company is negotiating to buy a brand identity firm and shopping for businesses to complement its events, sports, and telemarketing expertise. Ha-Lo plans to build a soup-to-nuts brand marketing business from the execution end up. Upshot brings Ha-Lo a strategic and creative reputation, and access to consumers via events.

“Upshot helps us get to a higher level in clients’ decision process,” says Ha-Lo president-ceo Lou Weisbach. “Our goal is to be more integral in the planning process” and handle campaigns from planning through execution. Different disciplines “get us in to clients at a higher level, but none more so than promotion marketing,” Weisbach says.

Ha-Lo also gets Upshot’s enviable client roster, including Sony Electronics, Coca-Cola Co., Anheuser-Busch, Southwestern Bell Communications, and Procter & Gamble Cosmetics.

Still, jumping from fulfillment into strategy is a big leap. When Gage ceo Skip Gage merged a lettershop and travel agency with his 30-year-old fulfillment house in 1991, he pitched strategic services to longtime clients like P&G and General Mills. “They’d say ‘What do you know about strategy? You’re a fulfillment house,’ ” Belle recalls. “This was coming from people who had paid me to set strategy for them two years before.”

Old brands, even agency brands, die hard.

Solutions, please

New consumer attitudes have forced marketers to see brand equity as a solution, not just an emotional bond. “In the past, equity was a touchy-feely connection. Today it’s much more concrete,” says Jon Kramer, president of J. Brown/LMC Group, Stamford, CT. “Consumers don’t care how they feel about your brand – they want to know how your brand will solve their problems. These days, marketing is about using a call to action to get consumers into the habit of using your brand.”

That’s why co-marketing and solution selling are so hot right now. Co-marketing marries brand image, retailer image, and a call to action. Solution selling through store “departments” like Johnson & Johnson’s Just for Women Center and Gilette Co.’s Men’s Grooming Center puts brands in context with consumer needs. Both strategies address retailers and consumers, and tap trade marketing and consumer ad budgets.

“Promotion is moving both up and down the food chain, expanding its importance in the marketing set,” says True North’s Bray[mentioned above?]. “Co-marketing cuts into trade dollars at the low end and is eating into ad dollars at the high end as it reinforces brand equity.”

Ad giant Saatchi & Saatchi bought its way into co-marketing this spring, purchasing GMG, Philadelphia, to serve General Mills and pitch P&G’s co-marketing business. (The shop was renamed Saatchi & Saatchi Co-marketing Services, and is moving to New York.)

“A number of our packaged goods clients already are spending a lot of money, or soon will be, on co-marketing. It’s budgets that we would lose from our normal relationships,” says Saatchi & Saatchi vice chairman Tony Dalton. Clients like P&G and Mills were spending more on co-marketing TV via smaller agencies. Since Saatchi wasn’t doing retailer-tagged TV spots, “I could see where that money could be taken from the brand advertising we were doing.”

In Dec. ’97, while Saatchi was negotiating the GMG buyout, General Mills asked the agency to pitch its co-marketing business. “The good thing was, I had spent four months looking at the marketplace, so at least I knew how it [co-marketing] worked, but I couldn’t say we had a partner,” Dalton says.

Saatchi scouted for a year to fill its “gap in knowledge of the retail marketplace,” either by hiring pros, or tapping a co-marketing shop through acquisition or alliance. It’s the third discipline Saatchi added in the last year: The agency also started up Saatchi & Saatchi Darwin Digital, a digital marketing company that evolved out of its interactive division; and allied with Lieber Levett Koenig Farese Babcock, New York, for database and relationship marketing. Dalton is eyeing other disciplines, too, like sports and events marketing, and digital TV. “It adds to your credibility when you recognize things beyond that which you’re traditionally known for,” he says.

Same partners, new music Other holding companies are rearranging their promotion shops. In June True North Communications, New York, grouped its promotion agencies including Market Growth Resources, Wilton, CT, and McCracken Brooks Communications, Minneapolis, in a new unit dubbed the Promotion Services Group. Each shop continues to run independently, but will cross-sell services to existing and new clients. MGR exec Wes Bray was named president of the group, with the mandate to improve each unit’s profitability and quality of work, cross-sell services, and shop for other agencies to buy.

“If we had been like this [a multi-agency conglomerate] six months ago, we would have fared better in Kraft’s review,” Bray says. “MGR and McCracken Brooks weren’t considered full-service enough for the business.”

MGR also lost out in Miller Brewing Co.’s consolidation last year, when Miller parceled its $35 million in promos to Zipatoni, St. Louis, and GMR Marketing, New Berlin, WI. “Clients are looking for agencies with a wide range of complementary services,” Bray adds.

Bray says “cross-selling” the shops to a wide range of clients is better than pitching a single, integrated unit to fewer marketers. Client conflict “is a real issue, so people have to understand these are free-standing companies. To position them all together works against us,” Bray explains.

The group includes design shop Peterson Group and sports marketer Properties Group, both New York, and Wilton-based Performance Media, spun off from MGR to handle co-op media buys. True North’s Impact Communications Group, Chicago, was not bundled in, and will continue to operate separately as sister shop to Foote, Cone & Belding, Chicago.

TLP is reaching into parent Omnicom’s vast international network for agency partners overseas. The Dallas agency launched TLPlanet this summer, an alliance of agencies to execute global strategies set by TLP’s Global Brand Trust – basically a global Rolodex of individuals with strong creative reputations. The system already has executed promos for Citibank’s sponsorship of Elton John’s world tour, and Pepsi International’s soccer events. TLPlanet’s axis is Wilton, CT, ruled by president David Marchi, and branding runs deep: TLP wants a global brand the same way its clients do.

So does Draft Worldwide. The Chicago-based direct-marketing giant puts the Draft moniker on everything it buys, including promo shops Lee Hill and MCA and, most recently, events marketing firm KBA, Chicago. “Clients made the ‘ugly stepchild’ syndrome go away because they demanded results,” says ceo Howard Draft. The agency is doing more one-to-one marketing in locations unique to target audiences, like bars, ino order to “turn the marketing message into more of a lifestyle element,” Draft says.

To buy or not to buy The strong economy has helped fuel the agency buying spree. “There’s too much money in the market not to consolidate, at least until the economy heads south,” says Gage’s Belle.

Frankel is debating whether home-grown divisions like Frankel Direct, Siren Technologies and Frankly Packaged are the best way to diversify. The agency benchmarked competitors to decide if it should buy existing businesses in digital technology, sports and design. “We thought traditional promo agencies were our competition, but we need to look more broadly than that,” says Frankel’s Roach. “Niche players are coming from underneath, and huge global players from the top. If we’re not careful, we’ll get sandwiched in between.”

The flurry of acquisitions add a sense of urgency: “If you don’t buy now, are you left with the dregs?” Roach challenges.

Home-grown “is good enough for now,” says Mack. “But we have our eyes open in areas that may move more quickly, like technology, where acquisition makes more sense.” Frankel’s ambivalence about going public wouldn’t scotch a deal: “We’re big enough to raise capital without an IPO,” Mack says.

When agencies aren’t courting, they’re often elbowing each other at the conference table.

Agency execs say they’re happy to work with ad shops or other promo shops, as long as the client clearly defines each role. If responsibilities overlap too much, they’re reluctant to share work.

“It creates some conflict as advertising steps into marketing strategy and promotion into brand strategy,” says Mack. “The client has to manage the process.”

Zipatoni, St. Louis, often meets directly with ad shop Fallon McElligott, Minneapolis, on Miller business. OLE QUOTE TK HERE. WCJ asks clients to introduce it to lead ad agencies. That gives WCJ a better overview of the brand, and opens a direct conversation between agencies. It’s easier to integrate creative that way, like the Godzilla tie-in that Chiat/Day and WCJ did this summer for Taco Bell. “Don’t put the client in the position to play traffic cop,” Deutsch advises. After all, your competitor today may be your colleague tomorrow.

So: Are ads dying? No, but the box around them is.

“Five years from now there will be a blur between the TV and the computer. At that point, what is ‘traditional advertising’?” posits Mack. “And five years from now promotion will be more interactive, more one-to-one. It’s up to marketers to understand the merging of what has been seen as separate disciplines.”

It begs a final question: Can brand management deliver on the Oz-like promise of seamless marketing? Can we all just get along?

Kraft has just finished a major review and consolidation of its $500 million promotion business, winnowing its list of 30 full-service promo agencies to TK. Reviews of co-marketing, ethnic, and event marketing agencies are likely to follow.

The summer review was part of Kraft’s 18-month-old Project Renaissance initiative to make the $X billion company “a world-class promotion organization,” says Wendy Kritt, director of of corporate and consumer promotions. Project Renaissance is part of Kraft’s

corporate-wide goal set by president Bob Eckert: Become the undisputed leader in food.

With that in mind, Kraft asked promo shops in its review some unusual questions. “We asked them ‘How do you define world-class? How will you help Kraft become the leader?’ ” Kritt says. “We changed from asking how agencies would work on our brands to asking how they would help us grow the entire company.”

The agency consolidation has three goals. First, Kraft wants “bigger and better ideas, more innovation from our agencies and ourselves,” Kritt says. Second, it named agencies of record to strengthen relationships between a brand team and its advertising and promotion agencies. Third, Kraft wants to save money. The company continues to boost promotion budgets and shift more dollars to the consumer side from trade. Streamlining assignments makes spending more efficient.

Kritt headed up the review with input from promotion directors at each of its six divisions and in the corporate Marketing Services unit. Brand managers consult with promo planners in their division to set campaigns; Kraft has about 100 promo planners across the company, 20 of them on the corporate level.

A source outside Kraft says some promotion managers felt blindsided by the review. An internal announcement in June was the first they heard of it, and some were upset at being dictated which shops to work with, the source says.

Promo planners have less control over agency assignments than they did in the past, when they bid out projects. There’s been some grumbling over that, Kritt admits, but “people see what their ultimate benefits are. We’re trying to divorce the decision-making from personalities and relationships, and focus on the business. That has led to some tough decisions.”

As part of its review, Kraft benchmarked the promotion industry as a whole, studying agency cost structures. Some shops were uncomfortable giving what they considered sensitive information like salaries, especially to an outside consultancy that vetted shops for Kraft. The consultancy does promotion work, so some shops felt as though they were telling sensitive details to a competitor.

Doling out $500 million to agencies of record makes a company do its homework rigorously. “Agencies need to own the brand as much as our internal people do,” Kritt says. “They need to live and breathe our products the way we do.”

Naming promotion agencies of record will foster tighter relationships with ad shops, Kritt adds. “Agencies are working together more than ever. Openly sharing information is the key to getting [our agencies] to realize they’re on the same team with us.”

That may be a tougher sell to Kraft’s own promo planners. Still, if Kraft can get all constituents to buy into the streamlined system, it could bring some powerful consumer campaigns to retailers and buff up the marketing polish of its sales pitch.

Advertising holding companies are busy buying below-the-line, while promotion-related companies buy their way into integration. Here are some of the major purchases redefining the landscape in the past year:

* AHL, Atlanta, buys Gage Marketing Support Services Group, Minneapolis, to grow its fulfillment business; Gage gets $81 million to buy research, promotion and direct marketing businesses (July 98)

* Premiums giant Ha-Lo Industries, Niles, IL, buys Upshot, Chicago, to add strategic services. Ha-Lo is negotiating to buy a brand identity firm, and shopping for other agencies (June 98)

* Promo shop Integer Group, Denver, merges with ad shop Kragie/Newell, Des Moines, IA (Oct. 97), buys Karsh & Hagan, Denver, to add advertising (June 98)

* Saatchi & Saatchi, New York, buys GMG Marketing, Philadelphia, to pitch co-marketing business from current clients General Mills and P&G (March 98)

* Database and promotion firm Snyder Communications, buys hot ad shop Arnold Communications, Boston (March 98)

* Direct marketing giant Draft Worldwide, Chicago, buys promo shops Lee Hill, Chicago, and MCA, Westport, CT (XX 97)

* Aspen Marketing Group, Evergreen, CO, formed in April 97 by merger of promotional products suppliers Schmidt-Cannon International and Hanig & Co., buys Map Promotions, Culver City, CA, for event marketing and travel incentives (Sept. 97); JG Promotions, San Francisco, for full-service packaged goods promos, and the Ashten Product Line for promotional products (Oct. 97); Premium Source Merchandising, Los Angeles, for fast food and cosmetics work (Jan. 98); Corporate Trademarks, Alpharetta, GA, for corporate identity (April 98); and Phoneworks for phone-based interactive promos (July 98)

* Promotional products supplier Cyrk Inc., Gloucester, MA, buys Simon Marketing, Los Angeles, for strategy/creative and Tonkin Inc., Monroe, WA, for brand identity work (Spring 1997)