(Direct) The results are in, and they ain’t pretty.

E-mail marketers lack standard definitions of fundamental metrics. Worse still, most don’t measure anything meaningful at all about their e-mail campaigns, according to two recent studies.

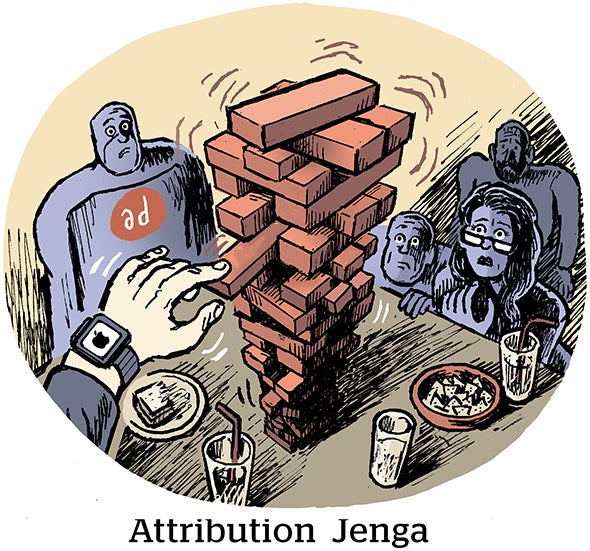

Even the most basic metric — delivery rate — has no hard definition, judging from a survey conducted by the deliverability roundtable of the Email Experience Council, a for-profit organization aimed at promoting standardization in the commercial e-mail industry.

For example, 79% of the e-mail service providers polled defined “delivered” by deducting all failures from the total messages mailed, while 21% calculated it by subtracting hard bounces — where an address no longer exists — from the total mailed.

E-mail marketers were in even further discord on this matter, as 63% reckoned “delivered” as the number of failures minus the total messages mailed, 11% as simply the total mailed, and 10% as only those e-mails that made it to recipients’ inboxes rather than their spam folders.

“That was the scariest finding of all,” says Deirdre Baird, roundtable chair and chief executive of deliverability consultancy Pivotal Veracity. “There’s a wide variation in how ‘delivered’ is calculated, and yet it’s central to everything we do in this business.”

But the confusion doesn’t end there. E-mail marketers also have no set way of determining so-called open rates. Half of the e-mail service providers figured it by dividing unique opens by total messages delivered while 73% of mailers used that method, the Email Experience Council noted.

The open-rate metric gets even murkier when one considers that an “open” is registered when the receiving computer calls for a graphic from the sending machine. The increasing prevalence of blocked graphics by inbox providers coupled with preview panes that may call for the graphics whether an e-mail has been opened or not makes it impossible to rely on the open rate as an accurate measure of how many e-mails in a given campaign were actually opened.

Then there are clickthrough rates. Should be simple enough to measure those, right? Well, not exactly, according to this study’s findings. About half of the mailers and e-mail service providers said they arrived at clickthrough rates by dividing clicks by the number of e-mails delivered. About a quarter said they did it by dividing clicks by opens. But some 8% of e-mail service providers and 14% of mailers said they come up with clickthrough rates yet another way: by dividing the number of clicks by the number mailed.

The debate over metrics standards may be academic, though, as a report from JupiterResearch found that the vast majority of e-mailers aren’t tracking what should be fairly standard gauges of a marketing program’s health.

When given a series of fairly obvious success-gauging metrics to choose from — such as revenue per subscriber, average order size and click-to-conversion rate — and asked which ones they use at least once a month, 50% of business-to-consumer direct marketers and 56% of business-to-business DMers picked “none of the above.”

For example, JupiterResearch discovered that just 8% of B-to-C and 12% of B-to-B DMers measure revenue per e-mail subscriber. And in a finding that should stun anyone with a traditional DM background, just 13% of B-to-C and 11% of B-to-B marketers said they track their e-mail customers’ average order size.

If these numbers weren’t bad enough, list-oriented metrics fared even worse. Just 2% of B-to-C and B-to-B DMers track their e-mail lists’ churn rate, and only 5% of B-to-C and 2% of B-to-B DMers keep tabs on the value of their e-mail addresses, according to JupiterResearch.

Instead of tracking revenue and list metrics, marketers tend to focus on things that may or may not matter, like bounce rate — which, by the way, could use a standard definition as well.

“Everybody’s running around saying, ‘Bounce rates are up and delivery rates are down,'” says David Daniels, the report’s lead author and vice president/research director at JupiterResearch. “But it might be that once you do your list analysis it doesn’t matter because this person isn’t a valuable subscriber to you. Or you might say, ‘Hey, it does matter, and we’re going to do a print mailer to this person or spend an extra minute with them to get their current e-mail address the next time they call our call center.'”

Daniels adds that e-mail’s current state of affairs probably will be foreign to anyone with a traditional DM background.

“I came out of the catalog direct marketing industry, and if I tried to make a decision that didn’t include some kind of RFM (recency, frequency and monetary value) analysis to know how many six- or 12-month buyers this book was going to hit, I’d have been marched out of the room,” he says. “It would have been that severe.”

These findings may indeed be jaw-droppers for mainstream DMers. It’s impossible to tell from the two studies, though, because neither broke out mailers by primary sales channel.

So what the heck is happening? Or a better question might be, why aren’t the right things happening?

For one thing, e-mail is relatively new as a commercial channel — about 10 years old. And for another, its practitioners tend to skew young, and they’re overworked and understaffed.

“I think the big syndrome here is ‘I’ve got to make the donuts,'” says Daniels, referring to Dunkin’ Donuts’ 15-year-long TV campaign in which sleepy-eyed Fred the Baker says “Time to make the donuts.”

“People are so mired in the production process and there’s a real shortage of talent. This industry is somewhat young and people are still inexperienced in this medium.”

Also, as has been the case since it emerged as a marketing channel, e-mail is a victim of its own whacked-out economics. It’s so cheap to deploy that it lacks the discipline of, say, cataloging, where the expense to print and mail essentially forces marketers to remove non-responders. Hence the ongoing spam problem, for instance.

Further contributing to this absence of discipline may be e-mail marketing’s astronomical return on investment. The channel returned $57.25 for every dollar spent on it in 2005, according to the Direct Marketing Association’s Power of Direct economic impact study released last October. Compare this with non-e-mail Internet marketing’s $22.52 and print catalogs’ $7.09 yield per dollar.

However, the industry apparently has awakened to the need for discipline. Last month Daniels headed an effort to set standards and announced a who’s-who list of backers. The E-mail Measurement Accuracy Coalition’s goal is to get everyone speaking the same language, publish some standards — particularly around deliverability — and disband by summer’s end.

Let the cleanup begin.