Kellogg plays up promotion to pull out of a sales crunch. Can the Grinch and Pokemon bring snap, crackle, and pop back to the cereal aisle?

It was the Frog Men that first won over Kevin Smith.

The red, green, and yellow U.S. Navy Frog Men that Kellogg Co. put in cereal boxes in 1954 captivated Smith as a kid. Drop a pinch of baking soda into the plastic figures’ secret compartments and they’d sink, then resurface and swim. They cost 25 cents each, and they had cool jobs: Torch Man, Demolitions Expert, Obstacle Scout.

“It’s magic to stick your hand in the bottom of a box and pull something out. That’s the kind of experience I want to give kids today,” says Smith, who grew up to become vp-consumer promotions at Kellogg Co.

Like the Frog Men who could dive and rise, Kellogg has been up and down, but is kicking back to the surface again. The Battle Creek, MI-based company is nearly halfway into a massive marketing push that ceo Carlos Gutierrez pledged late last year to roust the company from a two-and-a-half-year sales slump (January promo).

Kellogg has already made some gains in convenience foods, which will continue to drive the company’s profitability this year. But the breakfast giant has to right its flagship cereal business to make any potential success story complete. That’s where promotions will help most.

“You’ve just seen the beginning,” says Smith, referring to a summer Pokemon blitz and late 2000 tie-ins with Walt Disney Co. and Universal Pictures’ theatrical release of Dr. Seuss’ How the Grinch Stole Christmas. Those follow a first-quarter Cindy Crawford sweepstakes, Sesame Street collectible-fest, and an innovative tie-in with American Airlines on Kellogg’s ambitious promotion calendar, estimated at $150 million to $200 million. With 1999 ad spending flat at $176 million, it appears that Kellogg has plowed most of its 2000 budget increase into consumer promotions.

Smith won’t disclose his budget, saying only, “It’s gone up, but not at the expense of advertising. We’ve been selective, more efficient in our spending, to make it white-hot when we’re there.”

Sales results should kick in this quarter, says William Leach, an analyst with Donaldson, Lufkin & Jenrette in New York City. “Promotion may give them a newness they can’t get with products.”

“Our overall strategy is about experience, to reconnect with consumers in a way we haven’t done in the last couple of years,” says Marta Cyhan, senior manager-promotions.

Two elements influence Kellogg’s plan: chief executive Gutierrez and president John Cook. “First there’s old school – that’s Carlos [Gutierrez]. He’s an old cereal person. He’s been around the company,” Smith says. “He understands the power of the cereal package: It sits on the table and people read it. There’s great power there for promotions. We have a rich heritage in doing those kinds of promotions, and he wanted to get back to that.

“Second is John Cook, a new hire. He wanted us to look at consumers rather than product,” Smith explains. “We realized the targets we need to concentrate on are kids and, among adults, empty nesters.”

With that double focus, the big-picture plan calls for busy boxes with high-value premiums and mail-in offers; aggressive portfolio campaigns that link eight to 12 brands; account-specific marketing, a new tack for Kellogg; special packaging such as milk carton-style boxes for Special K Plus with calcium; and entertainment tie-ins.

One common thread is borrowed interest, a quick way to signal the added value that could prove crucial to rebuilding brand equity.

“They rely heavily on commodity products, and haven’t differentiated themselves as well as General Mills, which has more proprietary business and spends more on ads,” says analyst Leach.

Kellogg is playing catch-up after losing the top spot in the $7.7 billion cereal business to General Mills in late 1999. Kellogg keeps wrestling with General Mills for dominance as overall category sales remain soft, having slipped each year from 1995 through 1998. The cereal business is suffering from a prolonged drought of new products and the aftermath of price wars initiated by No. 3 manufacturer Post, which cut prices across the board by 20 percent in 1996; Kellogg and General Mills followed suit, thereby gutting their own margins – and marketing budgets.

Rising ingredient and labor costs strapped cereal makers even further, and hit Kellogg harder than its competitors. Kellogg didn’t have a safety net like Post, a division of Kraft Foods, or General Mills, whose portfolio runs from yogurt to Hamburger Helper.

Forced to cut advertising and consumer promotions, Kellogg relied heavily on trade promotion to carry its brands. It didn’t.

The turmoil kept the doors to Kellogg’s marketing department revolving. The company went through seven consumer promotions vps in nine years before Smith took over in April 1999.

Smith worked at Kellogg from 1983 to 1990, then left to form his own promotion agency, Densham & Smith Marketing Services, with Kellogg as a client. But Gutierrez courted him back. “I got to the point where I needed to do something different, and Carlos and John were looking for promotional expertise,” Smith says. “I was looking for a challenge.”

He has taken the challenge head-on. Special K was first out of the promo gate this year with a Makeover with Cindy sweepstakes that ran January through March. Five grand-prize winners got a trip to New York City for breakfast with Cindy Crawford and a full makeover by the supermodel’s personal trainer and stylists. Brigandi & Associates, Chicago, handled the promo; Leo Burnett USA, Chicago, provided ad support.

The sweeps had consumers “noticing the brand in a way they hadn’t before,” Cyhan says. “Some brands have lost touch with some of our consumers. This was one opportunity to connect with them and be noticed.”

Crawford topped Kellogg’s list of candidates who fit the Special K image. Kellogg happened to call shortly after Crawford gave birth, when she was working to get back into shape and eating the brand daily. “She said it was a real vote of confidence from Special K,” Cyhan explains. “She said, `I’ve been on the cover of every magazine out there, but I’ve never been on a cereal box.'”

Kellogg also ran two portfolio promos in the first quarter: A series of 24 Sesame Street mini-beans carried in 25 million boxes of eight kids’ cereals (Apple Jacks and Corn Flakes among them), and American Airlines frequent-flier miles on 10 adult brands (including Corn Flakes, All Bran, and Product 19). The American Dream mail-in offer runs through December, giving 100 miles per box. It’s the first-ever frequent flier deal for cereal. Gemcon Group, Chicago, handles.

Smith’s goal with portfolio campaigns is “to break through clutter, to create an event [across several brands] rather than a single brand, which rarely has the ability” to break through alone. Consumers have their own set of acceptable cereals, so portfolio events can hit a wider segment of consumers. “If we’re after kids and add all kid brands in, we’re certain to hit a wider percentage. The math is easy,” he says.

The trouble is, multi-brand campaigns can further blur the distinctions between brands, making them more of a commodity and easier to knock off. K-sentials, an umbrella ad campaign touting fortified cereal for kids, was canned in November after eight months because it didn’t catch on with consumers. (Boxes still carry the moniker.)

Still, it takes a brand of considerable size to warrant its own campaign. At Kellogg, that would be only a few cereals, such as Frosted Flakes and Special K, and convenience foods like Pop Tarts, Nutrigrain, and Eggo.

A PREMIUM ON PREMIUMS

Kellogg reviewed 150 premium agencies last year and chose a roster of preferred suppliers. That has helped the company significantly upgrade its offerings – beginning with the Sesame Street mini-beans, which were the most expensive in-pack premiums in the company’s history.

Kellogg also reviewed 100 promotion agencies last year and in August settled on six: DraftWorldwide, Chicago, was named its full-service consumer promotion agency, with Atlanta-based Garner & Nevins tapped to handle field execution; Brigandi, Clarion Marketing of Greenwich, CT, Noble & Associates of Springfield, MO, and The Marketing Department of Westport, CT, were named for concept development. (Davidson Marketing resigned the Kellogg business in 1998 over “philosophical differences.”)

“We have to look beyond just other cereal brands,” Smith says. “We’re competing every day with things like fast food, which has upscaled its premiums over the years. We’re competing against a different bar.”

Looking at QSR premiums made Kellogg realize that “kids have low expectations of cereal promotions, but significant expectations of what they like in premiums because of what they find at McDonald’s and Burger King,” Cyhan says. “We hadn’t been doing that caliber of premiums until this year.”

An upcoming premium effort leverages Kellogg’s eight-year-old NASCAR sponsorship. Eleven cereals will carry a mail-in offer for a die-cast replica of driver Terry Labonte’s car and a character car that corresponds to each cereal – Tony the Tiger for Frosted Flakes, Toucan Sam for Froot Loops. The cars are free via mail. “They’re actually free for a change,” Smith notes. “Over the years, `free’ has come to mean `with postage and handling.’ Kids have learned over time that `free’ doesn’t necessarily mean free. Well, it does now.”

Kellogg is also ramping up its account-specific work to garner retailer support. An overlay to the Sesame Street campaign complemented Kmart’s own Sesame Street line: A pocketed hanger to hold the Kellogg’s toys was sold exclusively through Kmart. Kellogg fulfilled the mail-in offer directly.

Account-specific “is one of Kevin’s mantras,” Cyhan says. “We’re trying to create better programs so they’re executed more effectively.” Tailored campaigns “tend to get us support, so it’s easier for brokers to work displays and in-store support,” Smith explains.

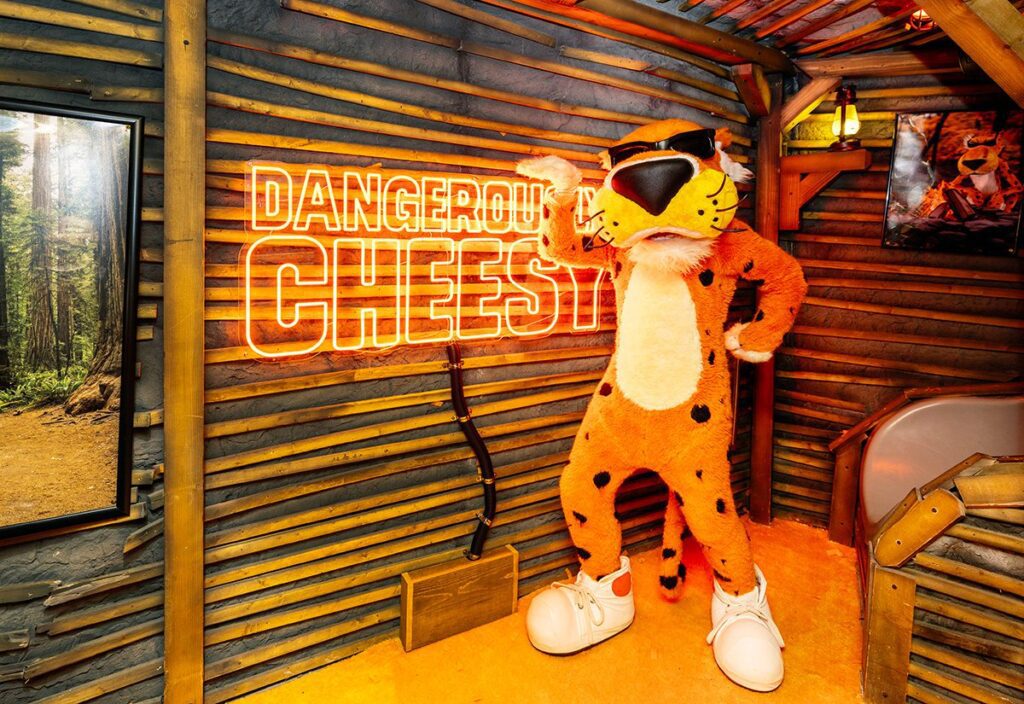

The proof may come with a Pokemon blitz starting next month. The campaign gives away high-value premiums through 15 brands, including non-cereal items. The effort centers on a new Pokemon cereal, a limited-time product that hits stores this month. DraftWorldwide handles, with Burnett on ad support.

Kellogg hired Dallas-based Marketing Specialists Corp. as its new brokerage in March to handle cereal, convenience foods, wholesome snacks, and frozen-food brands Eggo and Morningstar Farms (but not single-serve, grocery checkout, or c-store work). The shift signals a more aggressive pitch to grocers: Kellogg has worked with Marketing Specialists for 24 years, but consolidating now at the second-largest brokerage marshals all of its clout under one roof.

Future plans call for more promotional packaging like the milk carton-style boxes for Special K Plus with calcium. “That was a breakthrough for us,” Cyhan says. “Packaging is low-hanging fruit, one way we can connect with consumers. The first thing they see in the aisle is how we represent ourselves on our packages.”

Limited-time products will play an increasingly important role for Kellogg, after slack years with no new-product hits. With Pokemon, “the cereal rounds out the entire event,” extending consumer interest beyond premium offers, Smith says. Pokemon cereal is oat rings with four kinds of marshmallows shaped like characters. Bright blue, thirteen-ounce boxes will sell for $2.49.

A spring experiment labeled 3 Point Pops played to NCAA fever for six weeks with orange, basketball-shaped cereal in boxes featuring embossed basketballs on the front and a hoops game on the back (but no promo overlays behind it).

“It seems to be a winning strategy,” Smith says. “We’ll experiment, and learn over time where we need to be.”

As any good Obstacle Scout knows, it takes some navigating to regain your bearings. Kellogg may find its own in a familiar place: the bottom of the box.

Network

Network